ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY, & WILLIAMS, LLP v. FRANCISCO "FRANK" LOPEZ, No. 13-1026 (Tex. 2015)

Mandatory Lawfirm-Client Arbitration except for Fee Claims Against the Client: What if the client counterclaims under the civil barratry statute?

In

Royston, Rayzor, Vickery, & Williams LLP v Fancisco "Frank" Lopez, the Texas Supreme Court last Friday blessed a one-sided attorney-client retainer contract that would allow the lawfirm to force the client into arbitration on all manner of claims or complaints that the client may have against the law firm, but exempts the law firm from having to arbitrate a claim against the client for nonpayment of litigation expenses. In short, an attorney or lawfirm can avoid being sued by the client through an arbitration clause in the attorney-client agreement that covers all possible future disputes with one exception: it preserves the firm's right to sue the client to recover its costs (and by extension, its fees), which is the only plausible claim that the law firm could have against a client.

The firm might, of course, be sued, but it would be entitled to have the dispute diverted into a private arbitral forum by filing a motion to compel, relying on the legal services contract signed by the client. The Supreme Court did not find this objectionable,

and reversed the Thirteenth Court of Appeals, which had found that the specific agreement before the Court was so one-sided that it was unconscionable under the circumstances existing when the parties made the contract.

See Royston, Rayzor, Vickery & Williams, L.L.P. v. Lopez, 443 S.W.3d 196 (Tex. App.-Corpus Christi 2013, pet. filed) (orig. proceeding).

Justice Eva Guzman agreed on this disposition, but wrote a separate

concurring opinion addressing the implications for the ethical responsibilities of attorneys in their dealings with prospective clients.

ATTORNEY-CLIENT ARBITRATION

A LA CARTE

While the Supreme Court may have given a present to the legal profession by holding that such one-sided arbitration agreements are neither unconscionable nor against public policy --

which will no doubt be appreciated by Texas lawyers -- the ruling may also have opened up a can of worms, and may yet spur more appellate litigation over arbitration in the attorney-client context (and claim-splitting).

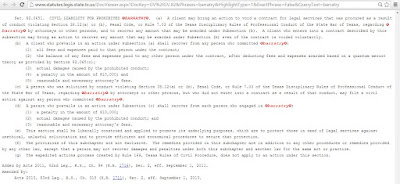

What if the client refuses to pay, the law firm sues for its fees, and the client responds that the fee claim is unenforceable because the contract was procured in violation of the barratry statute? This would not merely be an affirmative defense against the breach-of-contract claim as to the lawyer's or lawfirm's fees, but a counter-claim for damages, i.e. a claim by the client against the lawyer that is subject to arbitration. After all, the client may now recover statutory damages of $10,000.00, not just fee forfeiture.

|

| Texas Government Code Section 82.0651 Civil Liability for Prohibited Barratry |

Surely, a claim under Texas Government Code Section 82.0651 qualifies as a statutory cause of action for affirmative relief.

In a dispute implicating the civil barratry statute, then, the trial court would have to address the merits of the voidness claim as an affirmative defense to the legal service provider's fee claim that is exempted from arbitration under the attorney-client contract, but the arbitrator would have to decide the merits of the civil barratry claim that rests on the same facts because the client had agreed to to arbitrate all claims. What if court and arbitrator disagree in their respective determinations of whether barratry occurred? What if one holds that the contract was procured by barratry and is void, and the other one reaches the opposite conclusion?

Additionally, there is the matter of timing. Assuming the dispute between the lawfirm and the client is split into two parallel proceedings -- one in court, the other one the arbitral forum -- does it matter which one rules first on the voidness issue? Is that then

res judicata with respect to the other? Or is it only

res judicata (with immediate stalling effect on the parallel proceeding) if the arbitrator rules first, because there will be no appeal from an arbitratal award (except, when, in narrow circumstances, there are grounds to set aside the arbitration award)?

It would seem that the dominant jurisdiction doctrine cannot furnish an answer - and would not provide a basis for abatement - because the two fora do not have co-extensive authority under an arbitration agreement that makes some claims arbitrable but not others, - at least not in a scenario where both types of claims are present in the same dispute and are contemporaneously pursued, in the respective fora, but involve a common core of case-determinative facts.

Additionally, there may be disagreement on whether the statutory challenge to the attorney-client agreement under the civil barratry law is a challenge to the contract as a whole, including the arbitration provision that is part and parcel thereof, and what the arbitrator's role would be if the lawfirm argued that the barratry statute is unconstitutional (as a defense to the client's barratry claim pursued in the arbitral forum). Would the Attorney General have to be given an opportunity to defend the statute in the arbitral forum, and if so, would the arbitrator have the power to pass on constitutionality, even if the effect were to be limited to the case at hand? Would that be reviewable by a court, given that it involves a question of the validity to state law? Does an arbitrator exceed his or her power when passing on the merits of the constitutional argument?

The latter scenario is not implausible. A client might respond to a lawsuit for unpaid fees and litigate it in court without raising an issue about arbitration, and promptly file an arbitration claim against the lawfirm invoking the barratry statute. Assuming that the arbitrator does not have jurisdiction to declare a statute void, the law firm would have to defend that civil barratry claim on the merits, and would be deprived of the unconstitutionality defense. Or arguably so.

If an attorney or law firm has procured clients through marketing efforts that run afoul of the barratry statute, it would be in its interest to have the issued resolved in a private forum, and not create a public record, but does that advance the state's public policy? Is it fair to attorneys who lose business because of such unfair competition?

Which is merely part and parcel of the larger public policy question. Is it desirable, as a matter of public policy governing the practice of law, to remove barratry claims, legal malpractice claims and other claims of wrongful conduct brought against attorneys from the court system and divert them into private arbitration? The Supreme Court's ruling in

Royston v Lopez sends a message encouraging Texas lawyers and lawfirms to do just that.

There is a discernible trend afoot in the Texas Supreme Court of shrinking the role of the court system and reducing the availability of judicial remedies in the public adjudicatory forum provided for dispute resolution in the system of government.

In a similar vein, albeit based on different reasoning, the Supreme Court recently also approved the removal of claims against nursing homes (and, by extension, all medical malpractice claims) from the court system by blessing arbitration agreements in admission contracts even if they are not compliant with Texas law.

See The Fredericksburg Care Company L.P. v Juanita Perez et al. No. 13-0573.(Tex. Mar. 6, 2015). The Supreme Court denied the plaintiffs' motion for rehearing in that case, and in the companion cases, on the same day it handed down its decision in the attorney-client arbitration case.

MOTIONS FOR REHEARING OF THE FOLLOWING CAUSES DENIED

[June 26, 2015 Texas Supreme Court Order List]

13-0573

THE FREDERICKSBURG CARE COMPANY, L.P. v. JUANITA PEREZ, VIRGINIA GARCIA, PAUL ZAPATA, AND SYLVIA SANCHEZ, INDIVIDUALLY AND AS ALL HEIRS OF ELISA ZAPATA, DECEASED; from Bexar County; 4th Court of Appeals District (04-13-00111-CV,

406 SW3d 313, 06-26-13)

13-0576

THE WILLIAMSBURG CARE COMPANY, L.P. v. JESUSA ACOSTA, ET AL.; from Bexar County; 4th Court of Appeals District (04-13-00110-CV, 406 SW3d 711, 06-26-13)

13-0577

THE FREDERICKSBURG CARE COMPANY, L.P. v. BRENDA LIRA, AS REPRESENTATIVE OF THE ESTATE OF GUADALUPE QUESADA, DECEASED; from Bexar County; 4th Court of Appeals District (04-13-00112-CV, 407 SW3d 810, 06-26-13)

ATTORNEY-FEE ARBITRATION CASE INFO

(CONSOLIDATED INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL AND MANDAMUS PROCEEDING)

No. 13-1026

ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY, & WILLIAMS, LLP v. FRANCISCO "FRANK" LOPEZ; from Nueces County; 13th Court of Appeals District (13-11-00757-CV,

443 SW3d 196, 06-27-13)

The Court reverses the court of appeals' judgment and remands the case to the trial court.

- consolidated with -

No. 14-0109

IN RE ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY, & WILLIAMS, LLP; from Nueces County; 13th Court of Appeals District (13-11-00757-CV; 13-12-00023-CV, 443 SW3d 196, 06-27-13)

The Court denies the petition for writ of mandamus.

Justice Johnson delivered the opinion of the Court.

Justice Guzman delivered a concurring opinion, in which Justice Lehrmann and Justice Devine joined.

ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY, & WILLIAMS, LLP, Petitioner,

v.

FRANCISCO "FRANK" LOPEZ, Respondent.

IN RE ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY, & WILLIAMS, LLP, RELATOR.

No. 13-1026, Consolidated with No. 14-0109

Supreme Court of Texas.

Argued March 26, 2015.

Opinion delivered: June 26, 2015.

JUSTICE JOHNSON delivered the opinion of the Court.

JUSTICE GUZMAN filed a concurring opinion, in which JUSTICE LEHRMANN and JUSTICE DEVINE joined.

PHIL JOHNSON, Justice.

This interlocutory appeal involves the enforceability of an arbitration provision in an attorney-client employment contract. The provision specifies that the client and firm will arbitrate disputes that arise between them, except for claims made by the firm for recovery of its fees and expenses. After the underlying matter was settled, the client sued the firm. The trial court denied the firm's motion to order the dispute to arbitration. On interlocutory appeal, the court of appeals affirmed on the basis that the arbitration provision is substantively unconscionable and unenforceable.

We conclude that the client did not prove that either the arbitration provision is substantively unconscionable or any other defense to the arbitration provision. Accordingly, the judgment of the court of appeals is reversed and the cause is remanded to the trial court.

I. Background

Francisco Lopez hired Royston, Rayzor, Vickery, & Williams, LLP to represent him in a suit for divorce from his alleged common-law wife who won $11 million in the lottery. The two-page employment contract between Lopez and Royston, Rayzor contained the following arbitration provision:

While we would hope that no dispute would ever arise out of our representation or this Employment Contract, you and the firm agree that any disputes arising out of or connected with this agreement (including, but not limited to the services performed by any attorney under this agreement) shall be submitted to binding arbitration in Nueces County, Texas, in accordance with appropriate statutes of the State of Texas and the Commercial Arbitration Rules of the American Arbitration Association (except, however, that this does not apply to any claims made by the firm for the recovery of its fees and expenses).

Royston, Rayzor then filed suit for divorce on Lopez's behalf, the trial court ordered the parties in the divorce suit to mediation, and they settled. Lopez later sued Royston, Rayzor, claiming the firm induced him to accept an inadequate settlement. The firm moved to compel arbitration under both the Texas Arbitration Act (Arbitration Act), and common law. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE §§ 171.001-.098; see also L.H. Lacy Co. v. City of Lubbock, 559 S.W.2d 348, 351 (Tex. 1977) (noting that arbitration in Texas can be pursuant to statute or common law). The trial court held a hearing on the firm's motion and denied it. The only evidence introduced at the hearing was the employment contract.

Royston, Rayzor filed both an interlocutory appeal challenging the denial under the Arbitration Act, and an original proceeding seeking mandamus relief under common law. Royston, Rayzor, Vickery & Williams, L.L.P. v. Lopez, 443 S.W.3d 196 (Tex. App.-Corpus Christi 2013). The court of appeals affirmed the trial court's refusal to order arbitration under the Arbitration Act and denied mandamus relief. Id. at 209. The appeals court noted that Lopez did not challenge the existence of the arbitration provision or whether he agreed to it as part of his contract with Royston, Rayzor. Id. at 202. The court concluded that Lopez's claims were within the scope of the arbitration agreement and then moved on to Lopez's "several affirmative defenses to arbitration." Id. at 202-03. It first considered his assertion that the arbitration provision is substantively unconscionable because it viewed that issue as determinative. Id. at 203.

As an initial part of its analysis, the appeals court considered whether Lopez was required to show that the arbitration provision was both procedurally and substantively unconscionable. Id. at 203-04. It concluded that he needed to show only one or the other. Id. at 204. The court then concluded that the provision was so one-sided it was substantively unconscionable and unenforceable. Id. at 206.

In cause number 13-1026, Royston, Rayzor seeks relief from the court of appeals' judgment denying its interlocutory appeal, and in cause number 14-0109, it seeks mandamus relief directing the trial court to order arbitration. In 13-1026, the firm challenges the two determinations on which the court of appeals affirmed the trial court's order. It also urges that we consider Lopez's remaining defenses to arbitration even though the court of appeals did not reach them, hold that they are also invalid, reverse the court of appeals' judgment, and remand to the trial court with instructions that it order the case to arbitration.

Lopez responds by urging that we affirm the lower courts' decisions for several reasons: (1) the court of appeals correctly determined that an arbitration provision need not be both procedurally and substantively unconscionable to be unenforceable, and this provision is substantively unconscionable because it is excessively one-sided; (2) the arbitration provision was entered into in the context of Lopez's agreeing to become a client of the law firm, and given that context it violates public policy; (3) Lopez's status as a prospective client shifted the burden of proof to Royston, Rayzor to establish it met its ethical obligation to explain the effects of the arbitration provision to him and Royston, Rayzor did not do so; and (4) the arbitration provision is illusory because it allows Royston, Rayzor to avoid arbitration as to its fee disputes while requiring Lopez to arbitrate all his disputes.

II. Standard of Review

Arbitration agreements can be enforced under either statutory provisions or the common law. L.H. Lacy Co., 559 S.W.2d at 351. Under provisions of the Arbitration Act, a trial court's ruling on a motion to compel arbitration may be challenged by interlocutory appeal. TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 171.098. Under common law standards, the trial court's ruling on such a motion may be challenged by means of an original proceeding seeking mandamus relief. See L.H. Lacy Co., 559 S.W.2d at 351. The ultimate issue of whether an arbitration agreement is against public policy or unconscionable is a question of law for the court. See In re Poly-Am., L.P., 262 S.W.3d 337, 349 (Tex. 2008); J.M. Davidson, Inc. v. Webster, 128 S.W.3d 223, 229 (Tex. 2003). When public policy or unconscionability is the basis for denying a motion to compel arbitration and there are no factual disputes, the standard of review on appeal is de novo. See J.M. Davidson, 128 S.W.3d at 229.

III. Analysis

We first address the unconscionability issue which was the basis for the court of appeals' decision. Because we reverse on that issue and resolve the appeal by means of Royston, Rayzor's interlocutory appeal under the Arbitration Act, we do not address the firm's petition for writ of mandamus. See Walker v. Packer, 827 S.W.2d 833, 839 (Tex. 1992) (explaining that mandamus is a discretionary remedy that issues only to correct a clear abuse of discretion where no other adequate remedy by law exists). However, in the interest of judicial economy we also consider Royston, Rayzor's other potentially dispositive issues instead of remanding them to the court of appeals. See Rusk State Hosp. v. Black, 392 S.W.3d 88, 97 (Tex. 2012).

A. Unconscionability

Arbitration agreements may be either substantively or procedurally unconscionable, or both. See In re Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d 566, 572 (Tex. 2002) ("[C]ourts may consider both procedural and substantive unconscionability of an arbitration clause in evaluating the validity of an arbitration provision."). "Substantive unconscionability refers to the fairness of the arbitration provision itself, whereas procedural unconscionability refers to the circumstances surrounding adoption of the arbitration provision." In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d 672, 677 (Tex. 2006). Arbitration is strongly favored. J.M. Davidson, 128 S.W.3d at 227. So, once it is established that a valid arbitration agreement exists and that the claims in question are within the scope of the agreement, a presumption arises in favor of arbitrating those claims and the party opposing arbitration has the burden to prove a defense to arbitration. Id. The same principles apply to arbitration agreements between attorneys and clients. See In re Pham, 314 S.W.3d 520, 526-28 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2010, orig. proceeding [mand. denied]); Henry v. Gonzalez, 18 S.W.3d 684, 691 (Tex. App.-San Antonio 2000, pet. dism'd).

As noted previously, the court of appeals agreed with Lopez's argument that the agreement was substantively unconscionable. 443 S.W.3d at 209. In responding to the dissent, the court summarized and restated its conclusions as to unconscionability. Id. First, it reiterated that "arbitration clauses in attorney-client employment contracts are not presumptively unconscionable." Id. We agree with that statement. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 171.001 (providing that a written arbitration agreement is valid and enforceable and may be revoked only upon a ground that exists in law or equity for revocation of a contract). The prospective attorney-client relationship adds an overlay to attorney-client employment contracts, see Hoover Slovacek, L.L.P. v. Walton, 206 S.W.3d 557, 560-61 (Tex. 2006), but that overlay does not alter the basic principle that arbitration clauses in agreements are enforceable absent proof of a defense. Nor does it negate the principle that absent fraud, misrepresentation, or deceit, one who signs a contract is deemed to know and understand its contents and is bound by its terms. In re Bank One, N.A., 216 S.W.3d 825, 826 (Tex. 2007); In re McKinney, 167 S.W.3d 833, 835 (Tex. 2005) (holding that absent fraud, misrepresentation, or deceit, parties are bound by terms of the contract they signed, regardless of whether they read it or thought it had different terms); EZ Pawn Corp. v. Mancias, 934 S.W.2d 87, 90 (Tex. 1996) (holding that a party who has the opportunity to read an arbitration agreement and signs it is charged with knowing its contents).

Next, the court of appeals stated that Lopez did not have an evidentiary burden with respect to his contention that the arbitration provision was unconscionable. 443 S.W.3d at 209. We disagree. As our previous opinions have made clear, however, parties asserting defenses to arbitration clauses have the burden to prove the defenses—including unconscionability:

[U]nder Texas law, as with any other contract, agreements to arbitrate are valid unless grounds exist at law or in equity for revocation of the agreement. The burden of proving such a ground—such as fraud, unconscionability or voidness under public policy—falls on the party opposing the contract.

In re Poly-Am., 262 S.W.3d at 348 (internal citations omitted). In any event, Lopez relied on evidence—albeit a limited amount. Royston, Rayzor introduced the employment contract in support of its motion to compel arbitration. As we note more fully below, although Lopez did not offer any other evidence, he specifically relied on the language of the arbitration provision and the contract to support his defenses.

Third, the appeals court specified three reasons on which it based its "one-sidedness" conclusion: (1) the contract gave Royston, Rayzor the right to withdraw as counsel at any time for any reason; (2) the arbitration provision facially favored Royston, Rayzor by giving it the right to litigate claims for its fees and expenses while compelling Lopez to arbitrate all his disputes; and (3) the contract provided that regardless of the outcome of the claims in the underlying divorce action, Lopez would be solely responsible for all costs and expenses of that suit. 443 S.W.3d at 209. We address those reasons in turn, beginning with the first and third because they are based on provisions in the contract as opposed to provisions in the arbitration provision.

As the court of appeals noted, the attorney-client contract gave Royston, Rayzor the right to withdraw from representing Lopez at any time, for any reason, and it also required Lopez to pay costs and expenses of the divorce suit regardless of its outcome. But regardless of whether either or both of those provisions are so one-sided that the contract is unenforceable, a question we do not decide, they relate to the contract as a whole. And challenges relating to an entire contract will not invalidate an arbitration provision in the contract; rather, challenges to an arbitration provision in a contract must be directed specifically to that provision. See In re Labatt Food Serv., L.P., 279 S.W.3d 640, 647-48 (Tex. 2009); In re FirstMerit Bank, N.A., 52 S.W.3d 749, 756 (Tex. 2001) (noting that the defenses of unconscionability, duress, fraudulent inducement, and revocation must specifically relate to the arbitration portion of a contract, not the contract as a whole, if they are to defeat arbitration).

Which leaves the second reason the court of appeals gave for its conclusion that the arbitration provision was so one-sided as to be unconscionable: the provision favored Royston, Rayzor by excepting from the provision the claims it made for fees and expenses while compelling Lopez to arbitrate all his disputes. But, as the court of appeals pointed out earlier in its opinion, an arbitration agreement is not so one-sided as to be unconscionable just because certain claims are excepted from those to be arbitrated. 443 S.W.3d at 205-06. That is, an arbitration agreement that requires arbitration of one party's claims but does not require arbitration of the other party's claims is not so one-sided as to be unconscionable. See In re FirstMerit Bank, 52 S.W.3d at 757-58.

In support of the court of appeals' decision, Lopez argues that the language of the arbitration provision itself is evidence of its unconscionability. We disagree. In analyzing the provision for unconscionability, we begin with the rule that, as a party to the written agreement, Lopez is presumed to have knowledge of and understand its contents. In re Bank One, 216 S.W.3d at 826; In re McKinney, 167 S.W.3d at 835. Lopez's unconscionability claim is essentially that the provision is oppressive and grossly one-sided because it requires him to arbitrate all his claims against Royston, Rayzor, while allowing the firm to choose whether to litigate or arbitrate the only claim it realistically would have against him. However, Lopez misstates what the provision provides. The provision does no more than specify that claims of both parties arising from Royston, Rayzor's representation of Lopez must be resolved by arbitration, except for one category which is excluded from the provision. And as to claims in that category—any claims made by the firm for the recovery of its fees and expenses—the firm does not have a unilateral choice about arbitrating them. Rather, they are excluded from the arbitration provision and absent another agreement by which Lopez and the firm agree to arbitrate them, they are not subject to arbitration at the behest of either Lopez or the firm. The provision equally binds both parties to arbitrate claims within its scope and ensures that the same rules will apply to both parties: Texas statutes and rules of the American Arbitration Association. And as noted above, providing that one or more specified disputes are excepted from an arbitration agreement simply does not make the agreement so one-sided as to be unconscionable. See In re FirstMerit Bank, 52 S.W.3d at 757.

Additionally, Lopez does not focus on whether the arbitration provision deprives him of a substantive right, but even if he seriously contended that it did, it does not. A substantive right is generally understood to be "[a] right that can be protected or enforced by law; a right of substance rather than form." BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY 1349 (8th ed. 2004). The provision does not unduly burden Lopez's substantive rights merely because it requires some, but not all, claims between the parties to be arbitrated. Final and binding resolution of a dispute by arbitration is an accepted and adequate alternative to its resolution by a judge or jury.

And lastly, although Lopez counters Royston, Rayzor's contention that he offered no evidence of unconscionability, in part, by arguing that he did not need to present evidence because he was prevailing in the hearing on Royston, Rayzor's motion to compel arbitration, the record does not substantiate that position. The hearing transcript shows that after introducing the employment contract, Royston, Rayzor's counsel repeatedly argued that Lopez had the burden to prove a defense in order to avoid arbitration, and that he had not submitted any evidence to do so. The trial court questioned attorneys for both parties about the lack of evidence concerning whether Royston, Rayzor advised Lopez regarding the advantages and disadvantages of arbitration. Lopez's counsel did not intimate that evidence other than the contract existed or could be presented, and specified that Lopez was choosing to rely only on the language of the employment agreement and arbitration provision:

[W]e did present evidence. The evidence is their contract . . . . We choose to rely on the language of their contract . . . . Our position [is] the language in their contract itself with regard to [the] arbitration provision specifically does not put [Lopez] on notice of that and so we are relying on that evidence, . . . then I believe the burden shifts back to them to have to disprove that.

In sum, although the provision was one-sided in the sense that it excepted any fee claims by Royston, Razor from its scope, excepting that one type of dispute does not make the agreement so grossly one-sided so as to be unconscionable. See In re FirstMerit Bank, 52 S.W.3d at 757. The fact that Lopez was a prospective client of the firm until he entered into the employment contract does not change the principle.

We agree with Royston, Rayzor that Lopez did not prove the arbitration provision is substantively unconscionable. But if he had, then we agree with the court of appeals that it would be unenforceable regardless of whether it is procedurally unconscionable. An arbitration agreement is unenforceable if it is procedurally unconscionable, substantively unconscionable, or both. See In re Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d at 572.

We next consider Lopez's assertion that the arbitration provision is unenforceable because it violates public policy.

B. Public Policy

Attorney-client arbitration agreements are the subject of ongoing debate. See Jean Fleming Powers, Ethical Implications of Attorneys Requiring Clients to Submit Malpractice Claims to ADR, 38 S. TEX. L. REV. 625 (1997); Robert J. Kraemer, Attorney-Client Conundrum: The Use of Arbitration Agreements for Legal Malpractice in Texas, 33 ST. MARY'S L.J. 909 (2002). The debate arises because of two competing policies: the policy of holding attorneys to the highest level of ethical conduct and the policy of encouraging and enforcing arbitration agreements. See Hoover Slovacek, 206 S.W.3d at 560-61 (noting that lawyers are held to the highest ethical standards); J.M. Davidson, 128 S.W.3d at 227 (discussing the strong presumption in favor of arbitration agreements).

In Hoover Slovacek, the court of appeals held that a fee provision in an attorney-client agreement was so one-sided as to be unconscionable. 206 S.W.3d at 560. We agreed that the fee provision was unconscionable and unenforceable, but because it violated public policy. Id. at 563. Lopez asserts that considerations similar to those we applied in Hoover Slovacek apply here and make the arbitration provision unenforceable. In support of that argument he references several cases for the proposition that an attorney-client agreement is unenforceable as against public policy if it violates a Disciplinary Rule.[1] Lopez also relies on Opinion 586 of the Professional Ethics Committee in support of his argument, focusing on the following language:

The [Professional Ethics] Committee is of the opinion that [Rule 1.03(b)] applies when a lawyer asks a prospective client to agree to binding arbitration in an engagement agreement. In order to meet the requirements of Rule 1.03(b), the lawyer should explain the significant advantages and disadvantages of binding arbitration to the extent the lawyer reasonably believes is necessary for an informed decision by the client.

Tex. Comm. on Prof'l Ethics, Op. 586, 72 TEX. B.J. 128 (2009). In essence, Lopez argues that the standard in Disciplinary Rule 1.03(b), providing that "[a] lawyer shall explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make informed decisions regarding the representation," applies to prospective clients. He also argues that Royston, Rayzor had the burden to show that the explanations were made.

Royston, Rayzor maintains that the Disciplinary Rules and Professional Ethics Committee opinions are advisory and do not impose legal duties. The firm further argues that even if the rule and opinion apply in whole or part so it had a duty to explain something to Lopez, it was Lopez who had the burden to prove that the explanations were not made. We agree with the firm.

The Disciplinary Rules are not binding as to substantive law regarding attorneys, although they inform that law. In re Meador, 968 S.W.2d 346, 350 (Tex. 1998). Opinions of the Professional Ethics Committee carry less weight than do the Disciplinary Rules as to legal obligations of attorneys, but they are nevertheless advisory as to those obligations. See Tex. Comm. on Prof'l Ethics, Op. 586, 72 TEX. B.J. 128, 129 (2009) ("It is beyond the authority of this Committee to address questions of substantive law relating to the validity of arbitration clauses in agreements between lawyers and their clients."). Without addressing or diminishing to any degree the ethical obligations of attorneys, we are mindful that the parties to an agreement determine its terms, and courts must respect those terms as "sacred," absent compelling reasons to do otherwise. See Nafta Traders, Inc. v. Quinn, 339 S.W.3d 84, 95-96 (Tex. 2011) ("As a fundamental matter, Texas law recognizes and protects a broad freedom of contract. We have repeatedly said that `if there is one thing which more than another public policy requires it is that men of full age and competent understanding shall have the utmost liberty of contracting, and that their contracts when entered into freely and voluntarily shall be held sacred and shall be enforced by Courts of justice.'") (internal citations omitted).

It is by now axiomatic that legislative enactments generally establish public policy. See, e.g., id.; Tex. Commerce Bank, N.A. v. Grizzle, 96 S.W.3d 240, 250 (Tex. 2002). We have explained that:

Courts must exercise judicial restraint in deciding whether to hold arm's-length contracts void on public policy grounds: Public policy, some courts have said, is a term of vague and uncertain meaning, which it pertains to the law-making power to define, and courts are apt to encroach upon the domain of that branch of the government if they characterize a transaction as invalid because it is contrary to public policy, unless the transaction contravenes some positive statute or some well-established rule of law.

Lawrence v. CDB Servs., Inc., 44 S.W.3d 544, 553 (Tex. 2001), superseded by statute, Tex. Lab. Code § 406.033(e), as recognized in Austin v. Kroger Tex., L.P., ___ S.W.3d ___, ___ n. 18 (Tex. 2015) (formatting altered and internal citation omitted). And as relates to arbitration, the Legislature has clearly and directly indicated its intent that arbitration agreements be treated the same as other contracts. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 171.001. The principle is borne out by Cobb v. Stern, Miller & Higdon, the case Lopez first references to support his position. 305 S.W.3d at 41. There an attorney's contingent fee agreement was obtained by solicitation of a Louisiana resident in violation of Disciplinary Rules 5.03 and 7.03. Id. at 42-43. In holding that the contingent fee contract was voidable, the court of appeals relied on Texas Government Code § 82.065(b), which provided that "[a] contingent fee contract for legal services is voidable by the client if it is procured as a result of conduct violating the laws of this state or the Disciplinary Rules of the State Bar of Texas regarding barratry by attorneys or other persons." Id. at 42 (quoting Act of June 14, 1989, 71st Leg., R.S., ch. 866, § 3, sec. 82.065, 1989 Tex. Gen. Laws 3855, 3857 (amended 2011, 2013) (current version at TEX. GOV'T CODE § 82.065(b))) (emphasis added).

It is true that public policy is not solely established through legislative enactments and may be informed by the Disciplinary Rules. But where the Legislature has addressed a matter, as it has addressed the enforceability of arbitration provisions, we are constrained to defer to that expression of policy. See Liberty Mut. Ins. Co. v. Adcock, 412 S.W.3d 492, 499 (Tex. 2013). Accordingly, we decline to impose, as a matter of public policy, a legal requirement that attorneys explain to prospective clients, either orally or in writing, arbitration provisions in attorney-client employment agreements. Prospective clients who enter such contracts are legally protected to the same extent as other contracting parties from, for example, fraud, misrepresentation, or deceit in the contracting process. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 171.001. But prospective clients who sign attorney-client employment contracts containing arbitration provisions are deemed to know and understand the contracts' content and are bound by their terms on the same basis as are other contracting parties. See, e.g., In re McKinney, 167 S.W.3d at 835; EZ Pawn, 934 S.W.2d at 90.

Noting again that our decision is not intended to diminish or address any applicable ethical obligations of Royston, Rayzor, but rather is intended to address legal obligations between the parties, we conclude that the arbitration provision is not unenforceable on the basis that it violates public policy.

C. Illusory

Last, we address Lopez's claim that the arbitration provision is illusory because it binds Lopez to arbitrate all his claims against Royston, Rayzor, while excluding the only possible claim the firm might ever realistically make against him. Royston, Rayzor responds that Lopez's position completely misses the mark as to what comprises an illusory agreement. The firm urges that Lopez's illusory defense fails because consideration exists for the provision and Royston, Rayzor cannot avoid its promise to arbitrate all claims within the scope of the arbitration provision by, for example, unilaterally amending or terminating the provision. We agree with Royston, Rayzor.

Promises are illusory and unenforceable if they lack bargained-for consideration because they fail to bind the promisor. See In re 24R, Inc., 324 S.W.3d 564, 566-67 (Tex. 2010). According to the Restatement (Second) of Contracts:

Words of promise which by their terms make performance entirely optional with the "promisor" do not constitute a promise. . . . [Because while] there might theoretically be a bargain to pay for the utterance of the words, . . . in practice it is performance which is bargained for. Where the apparent assurance of performance is illusory, it is not consideration for a return promise.

RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS § 77 cmt. a (1981) (internal citations omitted). The same applies in the arbitration agreement context. An arbitration agreement is illusory if it binds one party to arbitrate, while allowing the other to choose whether to arbitrate. And an arbitration provision that is part of a larger underlying contract may be supported by the consideration supporting the underlying contract. In re AdvancePCS Health, L.P., 172 S.W.3d 603, 607 (Tex. 2005) ("[W]hen an arbitration clause is part of an underlying contract, the rest of the parties' agreement provides the consideration."). But such an arbitration provision remains illusory if the contract permits one party to legitimately avoid its promise to arbitrate, such as by unilaterally amending or terminating the arbitration provision and completely escaping arbitration. See In re 24R, 324 S.W.3d at 567; J.M. Davidson, 128 S.W.3d at 236. But the fact that the scope of an arbitration provision binds parties to arbitrate only certain disagreements does not make it illusory. See In re FirstMerit Bank, 52 S.W.3d at 757. Additionally, the mere fact that an arbitration clause is one-sided does not make it illusory. For instance, in In re AdvancePCS Health, L.P., we held that an arbitration agreement was not illusory despite the fact that the clause was one-sided because it allowed AdvancePCS to unilaterally modify the clause with 30-days' notice. 172 S.W.3d at 607-08. We determined that the clause obligated AdvancePCS to arbitrate claims falling within the 30-day window even if it modified the clause. Id.

The provision here binds both Royston, Rayzor and Lopez as to their claims other than those specifically excluded. It does not allow either party to unilaterally escape or modify the obligation to arbitrate covered claims. The mutually binding promises to arbitrate all disputes except the firm's claims for fees and expenses, as well as the underlying contract, provide sufficient consideration for the arbitration provision. Even as to the excluded claims, Royston, Rayzor cannot choose whether to arbitrate or litigate. As we explained above, those claims have to be litigated unless the firm and Lopez enter a new agreement to arbitrate them. Accordingly, the arbitration provision is not illusory.

IV. Conclusion

Lopez did not prove a defense to arbitration. We reverse the judgment of the court of appeals in cause number 13-1026 and remand that cause to the trial court for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. The petition for writ of mandamus in cause number 14-0109 is denied.

|

ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY, & WILLIAMS, LLP v. LOPEZ

(Texas Supreme Court 2015) |

JUSTICE EVA GUZMAN, joined by JUSTICE DEBRA LEHRMANN and JUSTICE JOHN DEVINE, concurring.

We have long observed that attorneys have an ethical obligation to "explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make informed decisions regarding the representation."[1] Today the Court decides whether the failure to timely and adequately explain the consequences of a mandatory arbitration provision in a legal services contract renders the arbitration agreement unenforceable. I agree with the Court that it does not and therefore fully join the Court's opinion. Moreover, I agree that Mr. Lopez failed to establish a defense to arbitration. I write separately, however, to emphasize the need for rules more specifically delineating the means and methods by which attorneys can discharge their ethical responsibilities in this context.

As written, the Disciplinary Rules do not speak directly to arbitration agreements; however, attorneys are under a general obligation to provide enough information about a matter so that the client can make informed decisions regarding the representation.[2] But this begs the questions: how much, to whom, in what form, does it depend on the relative sophistication of the parties, and if so, to what extent? The Court touches on best practices in this regard but, wisely, does not attempt to rewrite the rules governing lawyers' ethical obligations through judicial decree. Such reforms are more aptly suited to our rulemaking process, which invites the input of the bench and bar. This process will ensure we more thoroughly vet the applicable standards and will ultimately yield more predictability, uniformity, and certainty.

As a court, we are constitutionally and statutorily charged with promoting and enforcing ethical behavior by attorneys.[3] This is a solemn duty the Court has guarded for decades. As we have consistently recognized, the fiduciary nature of the attorney-client relationship imposes heightened duties and obligations on attorneys:

"In Texas, we hold attorneys to the highest standards of ethical conduct in their dealings with their clients. The duty is highest when the attorney contracts with his or her client or otherwise takes a position adverse to his or her client's interests. As Justice Cardozo observed, `[a fiduciary] is held to something stricter than the morals of the marketplace. Not honesty alone, but the punctilio of an honor the most sensitive, is then the standard of behavior.'"[4]

Attorneys must therefore demean themselves "`with inveterate honesty and loyalty, always keeping the client's best interest in mind.'"[5]

Arbitration agreements between attorneys and their clients are not inherently unethical.[6] Indeed, public policy strongly favors arbitration, and the benefits of arbitration are well recognized.[7] However, the use of arbitration agreements in legal services contracts raises special concerns, which may vary in nature or degree depending on the client's sophistication.

Vulnerable or unsophisticated clients are less likely to fully appreciate the implications of an arbitration agreement, understand the arbitration process and its procedures, or seek independent counsel regarding the costs and benefits of arbitration.[8] Certainly, an attorney has an ethical responsibility to fully and fairly discuss an arbitration agreement with a client, but the Disciplinary Rules lack clear guidance for discharging that responsibility. The potential for abuse at the earliest stages of the attorney-client relationship is a genuine concern.[9] Guidance is essential, but rather than articulating best-practices standards by judicial fiat, the rulemaking process provides a better forum for achieving clarity and precision.

With these additional thoughts, I join the Court's opinion.

[1] Johnson v. Brewer & Pritchard, P.C., 73 S.W.3d 193, 205 (Tex. 2002); Cobb v. Stern, Miller & Higdon, 305 S.W.3d 36, 41 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 2009, no pet.); Cruse v. O'Quinn, 273 S.W.3d 766, 771-76 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2008, pet. denied); Pickelner v. Adler, 229 S.W.3d 516, 530 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 2007, pet. denied); Lemond v. Jamail, 763 S.W.2d 910, 914 (Tex. App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 1988, writ denied); Quintero v. Jim Walter Homes, Inc., 709 S.W.2d 225, 229-30 (Tex. App.-Corpus Christi 1985, writ ref'd n.r.e.); Fleming v. Campbell, 537 S.W.2d 118, 119 (Tex. Civ. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 1976, writ ref'd n.r.e.).

[1] TEX. DISCIPLINARY RULES PROF'L CONDUCT R. 1.03(b), reprinted in TEX. GOV'T CODE, tit. 2, subtit. G, App. A (Tex. State Bar R. art. X, § 9).

[2] Id.; cf. id. R. 1.08(a) (prohibiting lawyer from entering into a business transaction with a client unless (1) the transaction and terms "are fair and reasonable to the client and are fully disclosed in a manner which can be reasonably understood by the client"; (2) the client has a reasonable opportunity to seek independent counsel; and (3) the client consents in writing).

[3] See TEX. CONST. art. V, § 31; TEX. GOV'T CODE §§ 81.024, .071-.072; see also TEX. RULES DISCIPLINARY P. preamble, reprinted in TEX. GOV'T CODE, tit. 2, subtit. G, App. A-1 ("The Supreme Court of Texas has the constitutional and statutory responsibility within the State for the lawyer discipline and disability system, and has inherent power to maintain appropriate standards of professional conduct . . . .").

[4] Hoover Slovacek LLP v. Walton, 206 S.W.3d 557, 560-61 (Tex. 2006) (quoting Lopez v. Muñoz, Hockema & Reed, L.L.P., 22 S.W.3d 857, 866-67 (Tex. 2000) (Gonzales, J., concurring and dissenting)) (alteration in original).

[5] Id. at 561.

[6] See TEX. COMM. ON PROF'L ETHICS, Op. 586, 72 Tex. B.J. 128 (2008) (binding arbitration provision is permissible in engagement agreement if the terms would not be unfair to a typical client, the client is aware of the significant advantages and disadvantages of arbitration, and the arbitration provision does not limit liability for malpractice); ABA COMM. ON ETHICS & PROF'L RESPONSIBILITY, Formal Op. 02-425 (2002) (holding similarly); see also RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF THE LAW GOVERNING LAWYERS § 54 cmt. b (acknowledging that arbitration agreements between lawyers and clients are permissible if "the client receives proper notice of the scope and effect of the agreement" and such agreements are enforceable in the relevant jurisdiction).

[7] See Jack B. Anglin Co., Inc. v. Tipps, 842 S.W.2d 266, 268 (Tex. 1992) (noting that arbitration agreements have been sanctioned in Texas since 1845); see also Steven Quiring, Attorney-Client Arbitration: A Search for Appropriate Guidelines for Pre-Dispute Agreements, 80 TEX. L. REV. 1213, 1217 (2002) (discussing advantages and disadvantages of arbitration).

[8] See Lopez, 22 S.W.3d at 867 (Gonzales, J., concurring and dissenting) ("A lawyer and client's negotiations are often imbalanced in favor of the lawyer because of information inequalities and the client's customary reliance on the lawyer's legal advice."); Jean Fleming Powers, Ethical Implications of Attorneys Requiring Clients to Submit Malpractice Claims to ADR, 38 S. TEX. L. REV. 625, 648 (1997).

[9] See, e.g., In re Pham, 314 S.W.3d 520, 528-29 (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2010, orig. proceeding) (Seymore, J., dissenting); Henry v. Gonzalez, 18 S.W.3d 684, 692-93 (Tex. App.-San Antonio 2000, pet. dism'd) (Hardberger, C.J., dissenting); cf. Lopez, 22 S.W.3d at 867 (Gonzales, J., concurring and dissenting) ("[A] lawyer should fully explain to the client the meaning and impact of any contract between them.").

OPINION OF THE COURT OF APPEALS BELOW (REVERSED)

443 S.W.3d 196 (2013)

ROYSTON, RAYZOR, VICKERY & WILLIAMS, L.L.P., Appellant,

v.

Francisco "Frank" LOPEZ, Appellee.

In re Royston, Rayzor, Vickery & Williams, LLP.

Nos. 13-11-00757-CV, 13-12-00023-CV.

Court of Appeals of Texas, Corpus Christi-Edinburg.

June 27, 2013.

Rehearing Overruled November 8, 2013.

Brandy M. Wingate, McAllen, Michael S. Lee, Corpus Christi, Sarah Pierce Cowen, McAllen, for Appellant.

Rene Rodriguez, Corpus Christi, Ross A. Sears II, Houston, for Appellee.

Before Chief Justice VALDEZ and Justices BENAVIDES and PERKES.

OPINION

Opinion by Justice BENAVIDES.

Royston, Rayzor, Vickery, & Williams, LLP ("Royston"), seeks to set aside an order denying its motion to compel arbitration by appeal in appellate cause number 13-11-00757-CV and by petition for writ of mandamus in appellate cause number 13-12-00023-CV. We affirm the order of the trial court in the appeal and we deny the petition for writ of mandamus.

I. BACKGROUND

Francisco "Frank" Lopez retained Royston to represent him regarding a common law marriage and divorce and to pursue claims against Lopez's alleged common law wife after she won $11 million playing the lottery. The "Employment Contract" between Lopez and Royston gave Royston a twenty percent contingency fee in any gross recovery before expenses, provided that Lopez was responsible for all costs and expenses regardless of outcome, and gave Royston the right to withdraw as counsel at any time for any reason. The agreement contained the following arbitration provision:

While we would hope that no dispute would ever arise out of our representation or this Employment Contract, you and the firm agree that any disputes arising out of or connected with this agreement (including, but not limited to the services performed by any attorney under this agreement) shall be submitted to binding arbitration in Nueces County, Texas, in accordance with appropriate statutes of the State of Texas and the Commercial Arbitration Rules of the American Arbitration Association (except, however, that this does not apply to any claims made by the firm for the recovery of its fees and expenses).

Royston filed suit on behalf of Lopez against his common-law wife; however, the suit was settled after court-ordered mediation. Lopez thereafter brought suit against Royston for malpractice, gross negligence, fraud, breach of contract, and negligent misrepresentation. Lopez asserted that Royston "provided alcoholic beverages" to him at the mediation, told him the settlement was in his best interests, and encouraged him to take a "meager" settlement, even though there was ample evidence that the parties had a common law marriage and an electronic message from Lopez's ex-wife showed that she had agreed "to a much larger settlement amount." Lopez asserted Royston "failed to zealously assert and prove" that he had damage claims that entitled him to either fifty percent of the lottery winnings as community property due to the then-existing common law marriage, or in the alternative, the "$3,200,000.00 he was entitled to pursuant to the text message from his ex-wife."

Royston moved to compel arbitration under the Texas Arbitration Act ("TAA") and, by supplemental motion, for arbitration under the common law. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM.CODE ANN. § 171.001-.098 (West 2011). Lopez responded to the motion to compel and supplemental motion raising numerous affirmative defenses to arbitration. After a hearing where the trial court considered the motions to compel and the responses thereto, which were supported only by the Employment Contract, 200*200 the trial court denied Royston's motion to compel arbitration.

This appeal and original proceeding ensued. By orders previously issued in these cases, the Court consolidated these two matters and ordered the underlying litigation to be stayed pending further order of this Court, or until the cases are finally decided. See TEX.R.APP. P. 29.5(b), 52.10(b). The matter has been fully briefed by both parties, and the matter has been submitted to the Court at oral argument.

By five issues, which we have summarized and restated, Royston contends that: (1) the trial court abused its discretion in denying the motion to compel arbitration; (2) a legal malpractice claim should not be considered to be a personal injury claim, and therefore subject to statutory requirements for arbitration agreements under the TAA;[1] (3) the trial court abused its discretion in denying arbitration if its decision was based on an advisory ethics opinion requiring that lawyers provide clients with information relative to litigation and arbitration before entering an arbitration agreement; (4) the arbitration agreement was not illusory; and (5) the arbitration agreement was not unconscionable.

II. MANDAMUS

Mandamus is an "extraordinary" remedy. In re Sw. Bell Tel. Co., L.P., 235 S.W.3d 619, 623 (Tex.2007) (orig. proceeding); see In re Team Rocket, L.P., 256 S.W.3d 257, 259 (Tex.2008) (orig. proceeding). To obtain mandamus relief, the relator must show that the trial court clearly abused its discretion and that the relator has no adequate remedy by appeal. In re Prudential Ins. Co. of Am., 148 S.W.3d 124, 135-36 (Tex.2004) (orig. proceeding); see In re McAllen Med. Ctr., Inc., 275 S.W.3d 458, 462 (Tex.2008) (orig. proceeding). A trial court abuses its discretion if it reaches a decision so arbitrary and unreasonable as to constitute a clear and prejudicial error of law, or if it clearly fails to correctly analyze or apply the law. In re Cerberus Capital Mgmt., L.P., 164 S.W.3d 379, 382 (Tex.2005) (orig. proceeding) (per curiam); Walker v. Packer, 827 S.W.2d 833, 839 (Tex.1992) (orig. proceeding). To satisfy the clear abuse of discretion standard, the relator must show that the trial court could "reasonably have reached only one decision." Liberty Nat'l Fire Ins. Co. v. Akin, 927 S.W.2d 627, 630 (Tex.1996) (quoting Walker, 827 S.W.2d at 840).

Arbitration clauses may be enforced under Texas common law. In re Swift Transp. Co., 311 S.W.3d 484, 491 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2009, orig. proceeding); In re Green Tree Servicing LLC, 275 S.W.3d 592, 599 (Tex.App.-Texarkana 2008, orig. proceeding); see L.H. Lacy Co. 201*201 v. City of Lubbock, 559 S.W.2d 348, 351-52 (Tex.1977) (common law arbitration and statutory arbitration are "cumulative" and part of a "dual system"); Carpenter v. N. River Ins. Co., 436 S.W.2d 549, 553 (Tex. Civ.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 1969, writ ref'd n.r.e.) ("In the many other states having arbitration statutes similar to our 1965 statute, it is almost uniformly held that the statutory remedy is cumulative and that the common law remedy remains available to those who choose to use it."). Mandamus is the appropriate procedure by which we may review the trial court's ruling on a motion to compel arbitration under the common law. See In re Swift Transp. Co., 311 S.W.3d at 491; In re Paris Packaging, 136 S.W.3d 723, 727 & n. 7 (Tex.App.-Texarkana 2004, orig. proceeding).

III. APPEAL

Under the TAA, a party may appeal an interlocutory order that denies an application to compel arbitration made under Section 171.021. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM.CODE ANN. § 171.098(a)(1) (West 2011). When reviewing an order denying arbitration under the TAA, we apply a de novo standard to legal determinations and a no evidence standard to factual determinations. PER Group, L.P. v. Dava Oncology, L.P., 294 S.W.3d 378, 384 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2009, no pet.); Trammell v. Galaxy Ranch Sch., L.P. (In re Trammell), 246 S.W.3d 815, 820 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2008, no pet.); TMI, Inc. v. Brooks, 225 S.W.3d 783, 791 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2007, pet. denied). In reviewing the trial court's factual determinations, we must credit favorable evidence if a reasonable fact finder could and disregard contrary evidence unless a reasonable fact finder could not. PER Group, L.P., 294 S.W.3d at 384; Trammell, 246 S.W.3d at 820 (citing Kroger Tex. Ltd. v. Suberu, 216 S.W.3d 788, 793 (Tex.2006); City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802, 807 (Tex.2005)); TMI, Inc., 225 S.W.3d at 791. However, when the facts relevant to the arbitration issue are not disputed, we are presented only with issues of law and we review the trial court's order de novo. PER Group, L.P., 294 S.W.3d at 384; Trammell, 246 S.W.3d at 820.

A party attempting to compel arbitration must first establish that the dispute in question falls within the scope of a valid arbitration agreement. J.M. Davidson, Inc. v. Webster, 128 S.W.3d 223, 227 (Tex.2003); TMI, Inc., 225 S.W.3d at 791; Cappadonna Elec. Mgmt. v. Cameron County, 180 S.W.3d 364, 370 (Tex.App.-Corpus Christi 2005, orig. proceeding). A court may not order arbitration in the absence of such an agreement. Cappadonna, 180 S.W.3d at 370 (citing Freis v. Canales, 877 S.W.2d 283, 284 (Tex.1994)). The parties' agreement to arbitrate must be clear. Mohamed v. Auto Nation USA Corp., 89 S.W.3d 830, 835 (Tex.App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 2002, no pet.) (combined appeal & orig. proceeding). If the party opposing arbitration denies the existence of an agreement to arbitrate, that issue is determined summarily by the court as a matter of law. TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM.CODE ANN. § 171.021(b); J.M. Davidson, Inc., 128 S.W.3d at 227. If the movant establishes that an arbitration agreement governs the dispute, the burden then shifts to the party opposing arbitration to establish a defense to the arbitration agreement. McReynolds v. Elston, 222 S.W.3d 731, 739 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2007, no pet.).

Courts may not order parties to arbitrate unless they have agreed to do so. See Freis, 877 S.W.2d at 284 ("While courts may enforce agreements to arbitrate disputes, arbitration cannot be ordered in the absence of such an agreement."); 202*202 Belmont Constructors, Inc. v. Lyondell Petrochemical Co., 896 S.W.2d 352, 356-57 (Tex.App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 1995, no writ) (combined appeal & orig. proceeding). Therefore, despite strong presumptions that favor arbitration, a valid agreement to arbitrate is a settled, threshold requirement to obtaining relief. See In re Kellogg Brown & Root, Inc., 166 S.W.3d 732, 737-38 (Tex.2005) (orig. proceeding); J.M. Davidson, Inc., 128 S.W.3d at 227.

Ordinary contract principles are applied to the determination of whether there is a valid agreement to arbitrate. J.M. Davidson, Inc., 128 S.W.3d at 227; see In re Bunzl U.S.A., Inc., 155 S.W.3d 202, 209 (Tex.App.-El Paso 2004, orig. proceeding). In determining the scope of the arbitration agreement, we focus on the petition's factual allegations rather than the legal causes of action asserted. See In re FirstMerit Bank, N.A., 52 S.W.3d 749, 754 (Tex.2001) (orig. proceeding) (decided under Federal Arbitration Act); PER Group, L.P., 294 S.W.3d at 386 (decided under TAA). Courts resolve any doubts about an arbitration agreement's scope in favor of arbitration. TMI, Inc., 225 S.W.3d at 791 (applying TAA). When parties agree to arbitrate and the agreement encompasses the claims asserted, the trial court must compel arbitration and stay litigation pending arbitration. See TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM.CODE ANN. § 171.021(b); Meyer v. WMCO-GP, LLC, 211 S.W.3d 302, 305 (Tex.2006); PER Group, L.P., 294 S.W.3d at 384.

Texas law embraces arbitration. The Texas Supreme Court has recognized arbitration as a potentially efficient, cost-effective, and speedy means of resolving disputes. See In re Olshan Found. Repair Co., 328 S.W.3d 883, 893 (Tex.2010) (orig. proceeding) ("we also recognize that arbitration is intended as a lower cost, efficient alternative to litigation"); In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d 337, 347 (Tex. 2008) (orig. proceeding) ("arbitration is intended to provide a lower-cost, expedited means to resolve disputes"); Jack B. Anglin Co. v. Tipps, 842 S.W.2d 266, 268 & n. 3, 269 (Tex.1992) ("the main benefits of arbitration lie in expedited and less expensive disposition of a dispute").

IV. ANALYSIS

Lopez does not dispute the existence of the Employment Contract or otherwise dispute that he signed the agreement. In reviewing the text of the agreement and considering that the parties signed it, we conclude that appellant has established an agreement to arbitrate. See In re Kellogg Brown & Root, Inc., 166 S.W.3d at 737. We further conclude that the claims at issue in this lawsuit fall within the scope of the agreement. See In re First Tex. Homes, Inc., 120 S.W.3d 868, 870 (Tex.2003) (orig. proceeding) (per curiam) (examining the scope of an arbitration agreement that applied to "all disputes between [the parties] ... arising out of this Agreement or other action performed ... by [a party to the agreement]"); see also Emerald Tex. Inc. v. Peel, 920 S.W.2d 398, 403 (Tex.App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 1996, no writ) ("If ... the [arbitration] clause is broad, arbitration should not be denied unless it can be said with positive assurance that the particular dispute is not covered."). The agreement requires arbitration of "any disputes arising out of or connected with this agreement (including, but not limited to the services performed by any attorney under this agreement)," and this provision squarely encompasses the malpractice claims raised against Royston.

Having concluded that the arbitration agreement was valid and the claims at issue were within the scope of the arbitration 203*203 agreement, we turn our consideration to appellee's defenses to the arbitration agreement. See J.M. Davidson, Inc., 128 S.W.3d at 227 (stating that if the trial court finds a valid agreement, the burden shifts to the party opposing arbitration to raise an affirmative defense to enforcing arbitration); In re H.E. Butt Grocery Co., 17 S.W.3d 360, 367 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2000, orig. proceeding); City of Alamo v. Garcia, 878 S.W.2d 664, 665 (Tex.App.-Corpus Christi 1994, no writ). Lopez raised several affirmative defenses to arbitration. Specifically, Lopez asserts, inter alia, that the arbitration agreement is substantively unconscionable. We address this issue first because we conclude that it is determinative of this proceeding.

Arbitration agreements are not inherently unconscionable. In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d 672, 678 (Tex.2006) (orig. proceeding). "Unconscionable contracts, however, whether relating to arbitration or not, are unenforceable under Texas law." In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d at 348-49. The TAA specifically acknowledges this defense and provides that a court may not enforce an arbitration agreement "if the court finds the agreement was unconscionable at the time the agreement was made." TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM.CODE ANN. § 171.022 (West 2005); see In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d at 677; In re Weeks Marine, Inc., 242 S.W.3d 849, 860-61 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2007, orig. proceeding).

According to the Texas Supreme Court, "[u]nconscionability is to be determined in light of a variety of factors, which aim to prevent oppression and unfair surprise; in general, a contract will be found unconscionable if it is grossly one sided." See In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d at 677 (citing DAN B. DOBBS, 2 LAW OF REMEDIES 703, 706 (2d ed. 1993); RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS § 208, cmt. a (1979)). Unconscionability is not subject to precise doctrinal definition and is instead determined in light of a variety of factors. In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d at 348-49. The determination regarding whether a contract or term is unconscionable is made in the light of its setting, purpose, and effect. Id. Relevant factors include weaknesses in the contracting process, fraud, and other invalidating causes, and the policy overlaps with rules which render particular bargains or terms unenforceable on grounds of public policy. Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d at 677 (citing RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS § 208, cmt. a (1979)). In considering an arbitration clause, allegations of unconscionability "must specifically relate to the [arbitration clause] itself, not the contract as a whole, if [unconscionability is] to defeat arbitration." In re FirstMerit Bank, N.A., 52 S.W.3d at 756.

The party asserting unconscionability bears the burden of proof. In re Turner Bros. Trucking Co., 8 S.W.3d 370, 376-77 (Tex.App.-Texarkana 1999, orig. proceeding). Whether a contract is contrary to public policy or unconscionable at the time it is formed is a question of law. In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d at 348-49; Hoover Slovacek LLP v. Walton, 206 S.W.3d 557, 562 (Tex.2006). Because a trial court has no discretion to determine what the law is or apply the law incorrectly, its clear failure to properly analyze or apply the law of unconscionability constitutes an abuse of discretion. In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d at 349; Walker, 827 S.W.2d at 840; In re Green Tree Servicing LLC, 275 S.W.3d at 602-03.

Unconscionability may be either procedural or substantive in nature. See In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 204*204 S.W.3d at 678. Generally speaking, procedural unconscionability refers to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the arbitration provision, and substantive unconscionability concerns the fairness of the arbitration provision itself. Id.; In re Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d 566, 571 (Tex. 2002) (orig. proceeding). More specifically, procedural unconscionability relates to the making or inducement of the contract, focusing on the facts surrounding the bargaining process. TMI, Inc., 225 S.W.3d at 792; see Labidi v. Sydow, 287 S.W.3d 922, 927 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2009, no pet.) (stating that the success or failure of an argument regarding procedural unconscionability is dependent upon the existence of facts which allegedly illustrate unconscionability). The test for substantive unconscionability is whether, "given the parties' general commercial background and the commercial needs of the particular trade or case, the clause involved is so one sided that it is unconscionable under the circumstances existing when the parties made the contract." In re FirstMerit Bank, 52 S.W.3d at 757; see In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d at 678. The principles of unconscionability do not negate a bargain because one party to the agreement may have been in a less advantageous bargaining position, but are instead applied to prevent unfair surprise or oppression. In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d at 679; In re FirstMerit Bank, 52 S.W.3d at 757.

As an initial matter, we note that Royston contends Lopez must show both procedural and substantive unconscionability, and, because he did not contend that the agreement was procedurally unconscionable, his argument must fail. We disagree. The Texas Supreme Court has expressly held that "courts may consider both procedural and substantive unconscionability of an arbitration clause in evaluating the validity of an arbitration provision." In re Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d at 572. The two types of unconscionability are distinct. See In re FirstMerit Bank, N.A., 52 S.W.3d at 756.

Agreements to arbitrate disputes between attorneys and clients are generally enforceable under Texas law; there is nothing per se unconscionable about an agreement to arbitrate such disputes and, in fact, Texas law has historically condoned agreements to resolve such disputes by arbitration. Cf. In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d 337, 348 (Tex. 2008) (discussing arbitration agreements between employers and employees); see, e.g., In re Pham (Pham v. Letney), 314 S.W.3d 520, 526 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2010, no pet.) (combined appeal & orig. proceeding); Chambers v. O'Quinn, 305 S.W.3d 141, 149 (Tex.App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 2009, pet. denied); Labidi, 287 S.W.3d at 929; In re Hartigan, 107 S.W.3d 684, 692 (Tex.App.-San Antonio 2003, orig. proceeding); Henry v. Gonzalez, 18 S.W.3d 684, 688-89 (Tex.App.-San Antonio 2000, pet. dism'd); Porter & Clements, L.L.P. v. Stone, 935 S.W.2d 217, 219-22 (Tex.App.-Houston [1st Dist.] 1996, no writ). The Houston Courts of Appeals have issued several opinions regarding attorney-client arbitration agreements and have taken a strong position in favor of such agreements. Pham, 314 S.W.3d at 526; Chambers, 305 S.W.3d at 149; Labidi, 287 S.W.3d at 927-28. Under this line of opinions, a fiduciary relationship between attorney and client does not exist before the client signs the employment contract containing the arbitration agreement, and therefore attorneys are not required to fully explain all implications of the arbitration clause. See, e.g., Pham, 205*205 314 S.W.3d at 526.[2] Further, courts should defer to the Legislature with regard to the imposition of any conditions on arbitration provisions between attorney and client. See id. at 528; Chambers, 305 S.W.3d at 149. We note that cases upholding attorney-client arbitration proceedings have engendered passionate and articulate dissenting opinions:

Notwithstanding the application of settled contract law and public policy favoring alternate dispute resolution, many respected jurists and lawyers oppose arbitration because it is not cost effective, disgorges unwary consumers of the right to a jury trial, and eliminates appellate review for errors of law. I remain a proponent of arbitration. However, when the legislature and rule-making authority in the legal profession fail to protect consumers of legal services, I believe the courts have an obligation to act because public perception of the legal profession's ability to self-police is not favorable.

Pham, 314 S.W.3d at 528-29 (Seymore, J., dissenting); see also Henry, 18 S.W.3d at 692 (Hardberger, C.J., dissenting).

In the instant case, Lopez contends that the arbitration agreement is unconscionable because it requires him to arbitrate all of his claims but allows Royston to litigate its claims regarding costs and expenses. The agreement provides that the parties are required to arbitrate "any disputes arising out of or connected with this agreement (including, but not limited to the services performed by any attorney under this agreement), except, however, that this does not apply to any claims made by the firm for the recovery of its fees and expenses." Royston concedes that "it is true that it is unlikely that Royston would ever have a claim against Lopez that was not a claim for fees."

The Texas Supreme Court has specifically addressed the concept of unconscionability where the terms of the arbitration agreement allow one party to litigate but force the other party to arbitrate:

The de los Santoses also argue that the agreement's terms are unconscionable because they force the weaker party to arbitrate their claims, while permitting the stronger party to litigate their claims. They point us to decisions in other jurisdictions that have found this type of clause to be unconscionable. Most federal courts, however, have rejected similar challenges on the grounds that an arbitration clause does not require mutuality of obligation, so long as the underlying contract is supported by adequate consideration. In any event, the basic test for unconscionability is 206*206 whether, given the parties' general commercial background and the commercial needs of the particular trade or case, the clause involved is so one-sided that it is unconscionable under the circumstances existing when the parties made the contract. The principle is one of preventing oppression and unfair surprise and not of disturbing allocation of risks because of superior bargaining power. Here, the Arbitration Addendum allows the bank to seek judicial relief to enforce its security agreement, recover the buyers' monetary loan obligation, and foreclose. Given the weight of federal precedent and the routine nature of mobile home financing agreements, we find that the Arbitration Addendum in this case, by excepting claims essentially protecting the bank's security interest, is not unconscionable. We also recognize that the plaintiffs are free to pursue their unconscionability defense in the arbitral forum.

In re FirstMerit Bank, N.A., 52 S.W.3d at 757 (internal citations and footnotes omitted). see also In re Poly-America, L.P., 262 S.W.3d at 348; In re Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d at 571.

Applying the basic test for unconscionability to the instant case, and examining the relevant factors, we conclude that the specific agreement before the Court is so one-sided that it is unconscionable under the circumstances existing when the parties made the contract. Significantly, neither In re FirstMerit Bank nor In re Poly-America involved the construction of a one-sided arbitration clause in the context of the creation of an attorney-client relationship. We further note that none of the cases proffered by the parties regarding the enforceability of arbitration clauses in attorney-client contracts concerned a clause allowing the attorneys to litigate but prohibiting their clients from doing so. Given the relationship between attorney and client, the relative expertise of lawyers in understanding the differences between arbitration and litigation and the relative costs thereof as compared to their clients, we find, under the specific facts of this case, that the arbitration agreement, by specifically excepting claims protecting Royston's fees and costs, is unconscionable. The terms of the arbitration provision are very unusual and, on their face, distinctly favor Royston over its relatively unsophisticated client, Lopez. See Sidley Austin Brown & Wood, LLP v. J.A. Green Dev. Corp., 327 S.W.3d 859, 865 (Tex.App.-Dallas 2010, no pet.). The arbitration agreement is not a "bilateral agreement to arbitrate" and is most definitely one-sided and oppressive. See In re Poly-America, 262 S.W.3d at 348-49; Labidi, 287 S.W.3d 922.

In reaching this conclusion, we note that Royston contends that the trial court abused its discretion in denying arbitration if its decision was based on an advisory ethics opinion requiring that lawyers provide clients with information relative to litigation and arbitration before entering an arbitration agreement. The opinion rendered by the Texas Ethics Commission suggests that it would be permissible under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct to include an arbitration clause in an attorney-client contract only if the client was made aware of the advantages and disadvantages of arbitration and had sufficient information to make an informed decision as to whether to include the clause:

In order for the client's agreement for arbitration to be effective, the Committee believes that the client must receive sufficient information about the differences between litigation and arbitration to permit the client to make an informed decision about whether to agree to binding 207*207 arbitration. While most of the duties owing from the lawyer-client relationship attach only after the creation of the lawyer-client relationship, some duties may attach before a lawyer-client relationship is established. See paragraph 12 of the Preamble to the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. Rule 1.03(b) provides that "[a] lawyer shall explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make informed decisions regarding the representation." The Committee is of the opinion that this Rule applies when a lawyer asks a prospective client to agree to binding arbitration in an engagement agreement. In order to meet the requirements of Rule 1.03(b), the lawyer should explain the significant advantages and disadvantages of binding arbitration to the extent the lawyer reasonably believes is necessary for an informed decision by the client. The scope of the explanation will depend on the sophistication, education and experience of the client. In the case of a highly sophisticated client such as a large business entity that frequently employs outside lawyers, no explanation at all may be necessary. In situations involving clients who are individuals or small businesses, the lawyer should normally advise the client of the following possible advantages and disadvantages of arbitration as compared to a judicial resolution of disputes: (1) the cost and time savings frequently found in arbitration, (2) the waiver of significant rights, such as the right to a jury trial, (3) the possible reduced level of discovery, (4) the relaxed application of the rules of evidence, and (5) the loss of the right to a judicial appeal because arbitration decisions can be challenged only on very limited grounds. The lawyer should also consider the desirability of advising the client of the following additional matters, which may be important to some clients: (1) the privacy of the arbitration process compared to a public trial; (2) the method for selecting arbitrators; and (3) the obligation, if any, of the client to pay some or all of the fees and costs of arbitration, if those expenses could be substantial. Although the disclosure should vary from client to client, depending on the particular circumstances, the overriding concem is that the lawyer should provide information necessary for the client to make an informed decision.

. . . .

It is permissible under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct to include in an engagement agreement with a client a provision, the terms of which would not be unfair to a typical client willing to agree to arbitration, requiring the binding arbitration of fee disputes and malpractice claims provided that (1) the client is aware of the significant advantages and disadvantages of arbitration and has sufficient information to permit the client to make an informed decision about whether to agree to the arbitration provision, and (2) the arbitration provision does not limit the lawyer's liability for malpractice.

See OP. TEX. ETHICS COMM'N No. 586 (2008). In the proceedings below, Lopez contended that this opinion supports the notion that for an arbitration clause in an attorney-client contract to be considered valid, an attorney must make sure that the client is fully informed regarding the clause's implications. However, as correctly noted by both the Ethics Commission and Royston, ethics opinions are concerned with matters of attorney discipline and are advisory rather than binding. Id. ("It is beyond the authority of this Committee to address questions of substantive law relating 208*208 to the validity of arbitration clauses in agreements between lawyers and their clients."); see Sidley Austin Brown & Wood, LLP, 327 S.W.3d at 866; Pham, 314 S.W.3d at 527-28; Labidi, 287 S.W.3d at 929. Accordingly, the trial court would have abused its discretion if it found the arbitration provision was unconscionable on this basis alone. We nevertheless conclude that the preceding ethics opinion, the disciplinary rules, and the public policy considerations surrounding the attorney-client relationship are some of the factors that can be considered when determining whether or not a contract is unconscionable. See In re Palm Harbor Homes, Inc., 195 S.W.3d at 677; see, e.g., Cruse v. O'Quinn, 273 S.W.3d 766, 775 (Tex.App.-Houston [14th Dist] 2008, pet. denied) (stating that the disciplinary rules do not give rise to private causes of action; however, a court may deem these rules to be an expression of public policy). In this regard, we agree with the recent analysis of Texas Supreme Court authority on the attorney-client relationship as expressed by the Dallas Court of Appeals: